Membrane receptors located on the surface of all cells enable them to respond to the arrival of messengers. Among these receptors, those that activate intracellular G proteins (or GPCRs) are the most numerous. They represent 3% of our coding genes and are the target of one-third of drugs. Their activity is therefore finely regulated, and their overactivation often leads to their entry into the cell, limiting the action of extracellular messengers and potentially causing the internalized receptor to generate new signals within the cell.

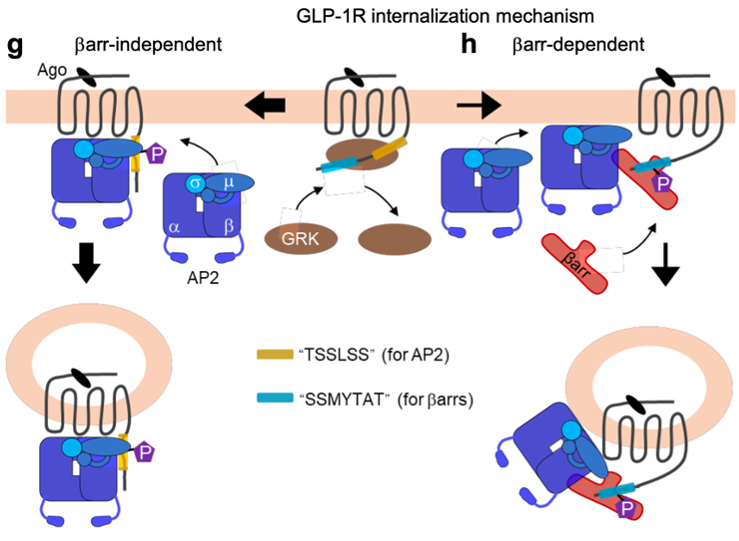

The most common mechanism leading to GPCR internalization involves their phosphorylation by specific kinases, GRKs, which allows the recruitment of a β-arrestin, the latter associating with the AP2 complex to send the receptor to clathrin-coated pits.

By analyzing the internalization properties of 60 GPCRs, Junke Liu in the team “Neuroreceptors, dynamics and functions” led by Philippe Rondard at IGF, in collaboration with Revvity, Magalie Ravier (co-team leader with Eric Renard of the team “Innovative therapeutics for diabetes” at IGF), Anne Goupil from Dassault System, and Carsten Hoffmann’s group in Germany, shows that many of them internalize even in the absence of β-arrestins. Among them is the receptor of GLP-1, a hormone that plays a key role in metabolism, so much so that activators of this receptor, initially developed for type 2 diabetes, are now widely used to combat the obesity “epidemic”. The study shows that GLP-1R can internalize via two distinct pathways, one of which is completely independent of β-arrestins and involves direct interaction between the AP2 complex and the receptor. The second pathway is more conventional. But why are there two internalization mechanisms? At this stage, we can only speculate. It is possible that the two mechanisms are involved in different conditions that have yet to be identified. Above all, it is possible that the receptor ends up in different intracellular vesicles, which may or may not allow intracellular signaling of the receptor, its recycling, or its degradation.

This work shows how unique each GPCR is and how important it is to challenge dogma.

This work has just been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Schematic representation of the two pathways for GLP-1 receptor internalization. On the left, direct interaction of the receptor with the AP2 complex leads to internalization independent of β-arrestins. On the right, the more traditional mechanism involving GRKs, the recruitment of β-arrestins and their association with AP2 to drive the receptor towards clathrin-coated pits.